27 September 2013

Let's Talk About Reasonable Budgets

As a consultant, I’m often asked to help in the initial stages of a

project to estimate “how big is the breadbox”. I completely understand

this need. A famous teacher once said, “Don’t begin until you count

the cost. For who would begin construction of a building without first

getting estimates and then checking to see if there is enough money to

pay the bills?”

"We can't offer fixed-scope pricing for work of an unknown complexity."

"I know……but in this case, how much would you charge?"

— Justin Searls (@searls) August 14, 2013I want to have these conversations with clients and customers because

it’s important that everyone understand what’s at stake. I think

it would be better though if instead of talking about an estimate we

talk about a budget. Let’s have the exact same conversation but say

“budget” every time instead of “estimate”.

Project Estimates versus Story Estimates

What do we even mean when we say “estimate”? We use that word in a lot

of different contexts. Up front we try to “estimate” how long it will

take to complete the project. Each iteration we try to “estimate” how

much we’ll get done that week. While planning we “estimate” how long a

single story will take to complete.

Maybe instead, we focus on “estimating” the complexity of a

story/project. “Is this story a beagle, doberman, or a great dane?”

Maybe we’re focusing on estimating risk.

I think there’s a lot of confusion in our industry from all the

different ways we use the word “estimate.”

Today I want to talk about guessing how much time or money it will

take to complete a project.

The Fallacy of Estimates

George Dinwiddie asks an interesting question, “What is the

right length for a

project?”.

If we execute the project perfectly, we’ll complete it in the ideal

amount of time. Estimating is the ability to guess that ideal amount

of time.

There are many factors that affect the length of a project. For

instance, hindsight might tell us if we’d tackled feature Z before we

tackled feature A things would have gone better. Maybe if we’d

included Jane on the project discussions, more we would have understood

that business function better and avoided problems. Maybe if we had

understood the new QuickMVC Javascript framework better we could have

built the front-end faster. Maybe if we hadn’t been stuck with older

technology on the back-end we could have delivered features faster and

more reliably.

George correctly points out that:

It is impossible to predict what set of alternatives will result in

the shortest schedule. There is no perfect way to run a project.

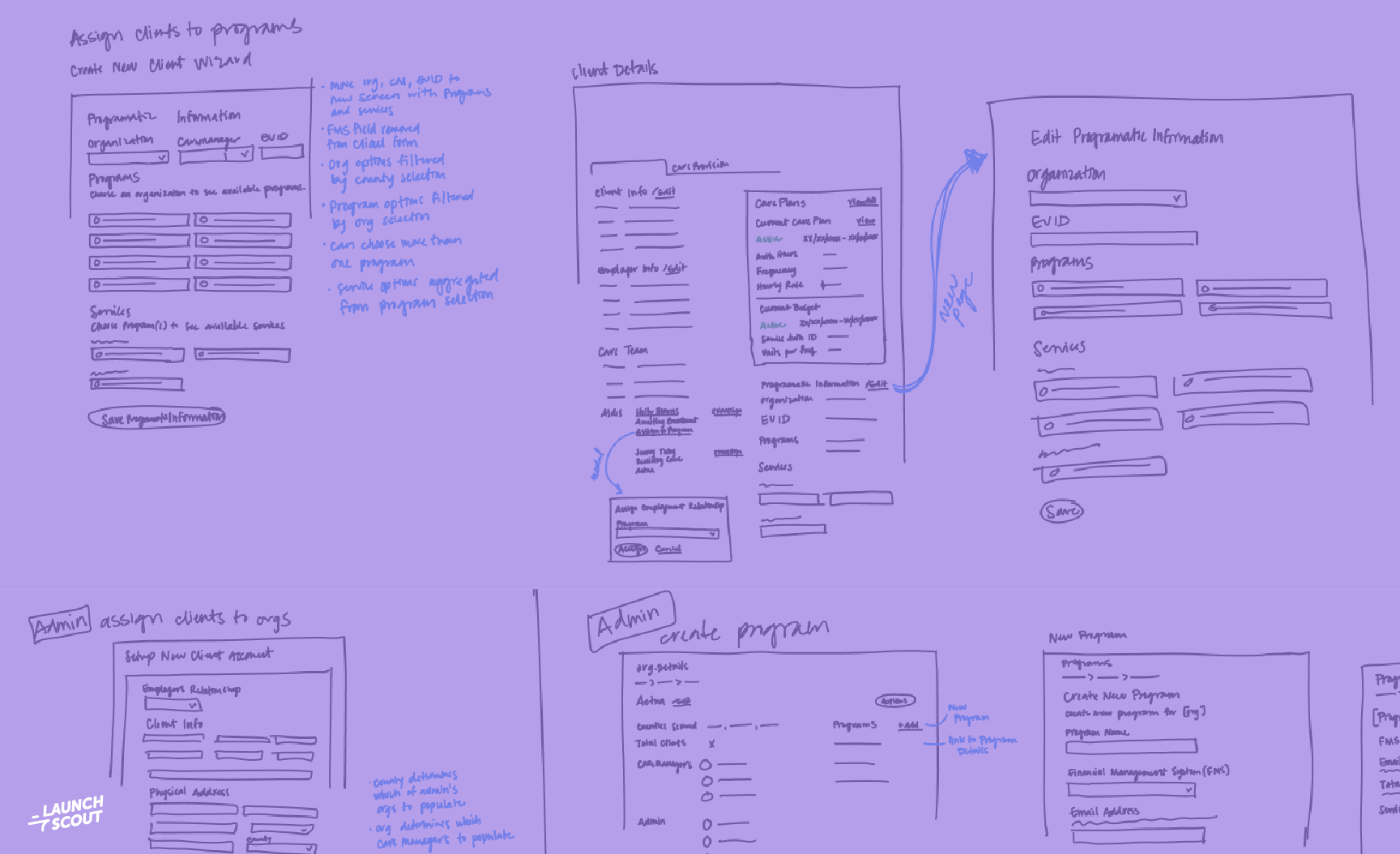

Start with Discovery

I think the best way to start a project is to have an extended

conversation about the project, it’s scope, risk factors, and time

line. Let’s build some mutual understanding about the business context

and the technical constraints.

There’s no way to get around it, the longer we work on a project the

more we’ll understand it. The inverse is also true, the less time

we’ve had to work on a project the less we understand it. What that

means is that the day we start the project we understand it the least.

This is as true for the team delivering the project as it is for those

who want it delivered. The day a client walks in with a

project idea asking for an estimate is the time when we all understand

the project the least.

At Gaslight we have a formula we use

for a week long discovery to ignite your best

ideas. Time and time

again this process has produced several “Ah-ha” moments. The goal here

is to have mutual, deep understanding of what we’re getting into.

Budgets vs Estimates

But how would the conversation be different if we talked about budgets

instead of estimates?

After we’ve done the project discovery, most clients want some kind of

an estimate. It seems reasonable to ask for one. We as engineers and

consultants, no matter how reluctant, feel obliged to offer this

estimate. Put yourself in the shoes of this business owner or manager

or entrepreneur. How can they evaluate the project if they don’t know

the estimate?

Recently, a client asked for an estimate and I was reluctant to

give one. The pressure was on. This client has a multi-million dollar

budget and our project was just part of that. How could he do proper

planning without an estimate?

I said we should have the conversation but replace the word “estimate”

with “budget”. My partner replied, “But we can’t budget for him.”

He’s exactly right! We can’t budget for him!

That’s why it’s important to have the conversation. The client often

can’t accurately predict the value the project will provide. But the

client should have a hunch. If the project isn’t valuable, we

shouldn’t do it – no matter the cost. We don’t know how hard or

complicated the project really is; but we should have a hunch. The

result of the conversation should be something like this:

If we could deliver these big, fuzzy features for this kind of

budget, it would be valuable.

Once we have an idea of what the budget is, as engineers and

consultants we can make a gut check to see if that’s reasonable. Can

we deliver for that budget? One of my heroes, Ron Jeffries, recently

said pretty much the same thing.

Let’s get started

But Ron went further with two excellent suggestions. Both involve

having a highly engaged “product owner” who really understands the

business.

The first he calls, “Good, But Not Ideal”. Based on a budget, pick a

date and some high priority objectives. Here’s the important part:

deliver towards those objectives every week until you hit your date.

That bears repeating: ship production quality software every week. You

don’t have to wait until the end to reap the rewards.

Here’s the “ideal” solution he presents: build something now. Just

pick a budget you’re willing to risk. Take a real product visionary

and have them spend a couple weeks one on one on one with a designer

and a developer. See what get’s built. Is it valuable? Is it worth

continuing? If it’s working, keep going. If it’s not working, stop.